by Sarah Child

Index

The Village and the Manors

Farms and Farming

The Poor

Education

Entertainment

Church and Chapel

Trinity Well

Families

World Wars 1 and 2

Buildings

Bibliography and Accreditation

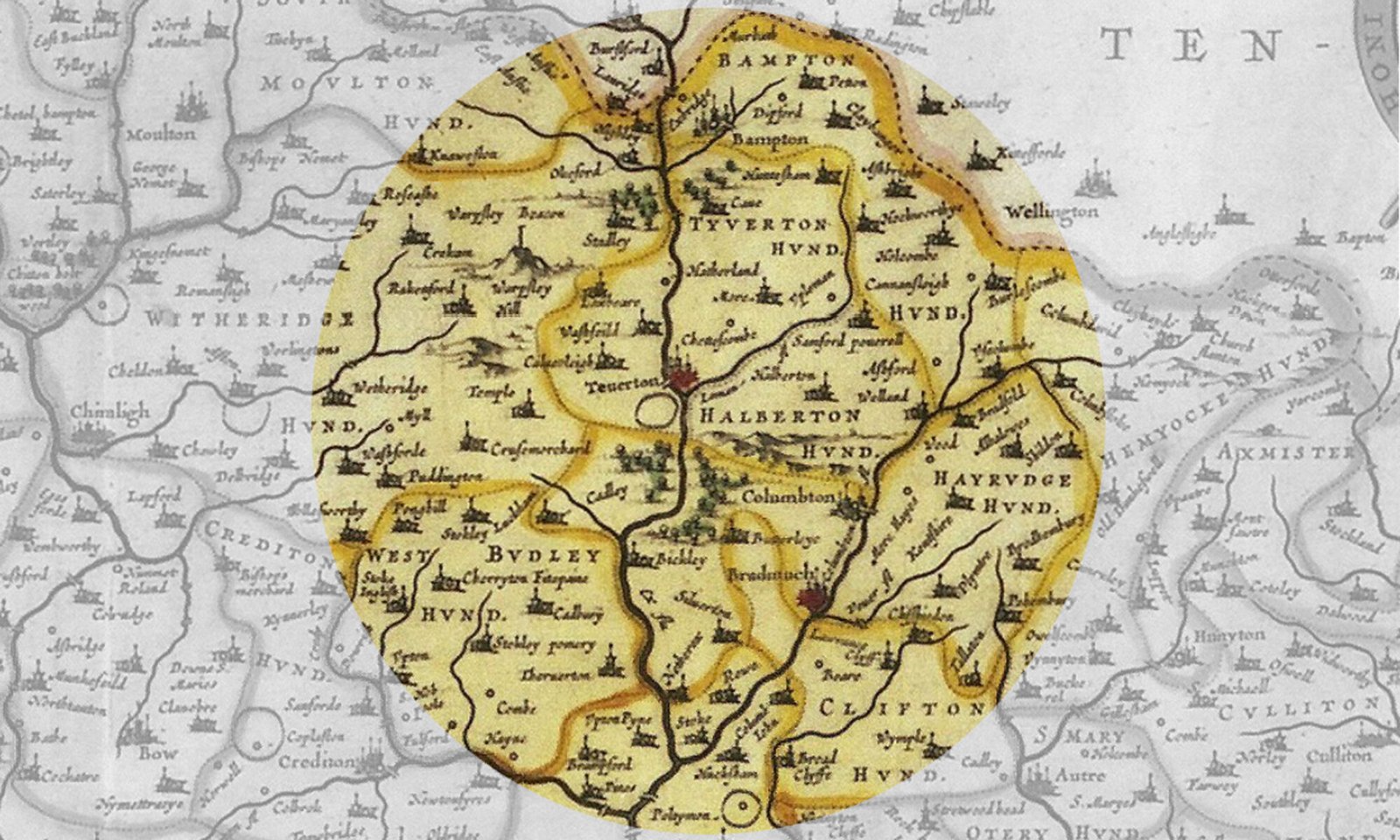

This is a much enlarged version of the 2009 first edition. Most parish histories are

approached chronologically, but the surprising wealth of documentary information which exists even for remote rural areas seems most interesting when broken up by subject. The first edition did not consider farming separately, which was odd since farming was and partly still is mainly what Rackenford life was about, or World War 1, which was the watershed between history and modern times. This one still ignores health, a subject illuminated by the church registers which show for example one in six children dying before their fifth birthday up to the late 19 th century, and a smallpox epidemic in 1731. It also leaves out law and order. Manorial records are not available, but the records of the Magistrates and the Assize courts from the 17 th century onwards show that there was never very much crime apart from thieving, swearing and minor assaults, with occasional incidents of infanticide and arson. It could however be mentioned here that the parish as a whole was prosecuted in 1812 and again in 1821 for its persistent neglect of its share of local roads. Rackenford Parish and its farms (before the A361 was built)

The Village and the Manors

Rackenford is a large parish with a small population, currently about one person to ten acres. On high ground, eight miles to the west of Tiverton, it is centred on a small village of 70 houses in which roughly half the population lives. In the middle of the village is Rackenford common. This is a likely survival of 11 acres of the mediaeval common field system; several of the village properties retained common rights to graze stock on the common within living memory, while ownership of the freehold remained with Rackenford manor until it was donated to the Parish Council in 1999.The village is ringed by a dozen farms and several smallholdings and lonely cottages. This has been the pattern since the Saxons settled here sometime in the 7th century, calling the place Rachenefode, which may mean a path between two fords – possibly those at Old Bell to the north and the crossing of the Little Dart below the village to the south. The settlement may be older than that; there are Bronze Age barrows in Templeton, just beyond the parish’s eastern boundary, and Berry Castle is the site of a Roman encampment in Witheridge, just across the boundary to the south west, so this has long been a populated area. When the Normans conquered the Saxons the parish consisted of six manorial holdings – Great Rackenford included the village and was much the biggest, with land for six ploughs and 60 sheep, while Little Rackenford, Sideham, Backstone, Bulworthy and Worthy were all rated at only one to three ploughs. Domesday Book shows a total of 29 families in all – 12 smallholders, 6 villagers and 11 slaves – in 1086. Great Rackenford expanded to take in some of the other holdings, which all survive as farms. Other farms – Canworthy, Middlecott, the Nutcotts, Thorne , Mogworthy – are all at least as old as the 13 th century, which saw a general expansion on to waste land. A Norman family called de Sideham were the owners of the main estate in the 12 th and 13 th centuries. Robert de Sideham made a successful application to the king in 1235 for the right to hold a fair every year on All Saints Day, and a market every Friday. 1 He must have hoped to develop Rackenford as a market town, since he also had it granted borough status. However the project never took off, although annual sheep and cattle markets were held (either side of the road below Town End) right up to the Second World War.The manor house was known as Cruwyshays, until changed to Rackenford Manor by a more snobbish owner in the 1930s (though possibly he was tired of spelling it). The Sideham family had ended with two daughters. One of these married a Cruwys of Cruwys Morchard and the other into a family that later merged with the Aclands, who originated from Landkey but by a series of judicious marriages became owners of large tracts of the west country. As a result, from the 14 th century much of Rackenford belonged to these two big estates, collecting rents from a distance, although the Cruwys family seem sometimes to have used the manor house as a home for married sons or younger brothers. In 1627 the Cruwys sold all their Rackenford lands, partly to their tenants. From then on ownership was more fragmented, though the owners of the main manor periodically reassembled much of the estate. The 18th century Lyddons for example owned 1300 acres including nine of the larger farms, and 18 cottages in the village, but all of this had to be sold in 1781 to pay the debts 2of William Lyddon, aged 24, owed to several of his neighbours. A Taunton solicitor, Edward Leigh, bought the estate in 1811 and rebuilt the house shortly afterwards, but sold the manor to Charles Devon, a Middlesex magistrate, in 1821. Since the time of the Cruwys it has seldom been owned by the same family for more than two generations, and often let or used for a country house rather than a permanent home. There are no other big houses in Rackenford except for the Rectory. Perhaps as a result Rackenford became a parish accustomed to running itself, a tradition which seems to have persisted up to the present day. It was also, until the building of the toll roads in the mid 18 th century, very isolated, linked by five miles of muddy track to the nearest significant village of Witheridge and further still from the market towns of Tiverton and South Molton. There are four or five Witheridge farms very close to the parish boundary whose residents have tended to relate to the Rackenford rather than the Witheridge community, but excluding these the population slowly doubled from the Domesday total to reach the 58 households recorded in 1664 for the Hearth Tax, suggesting a total of around 200 then. This was the pattern for the next 100 years or so, after which as elsewhere the population began to grow rapidly, reaching ara peak in the mid 19 th century before dropping down again sharply over the next 40 years. Since then it has grown slowly

to about 400 today.

Farms and Farming

For most of its recorded history, the parish economy consisted mainly of small to mediumfarms. Four of these were relatively large at 200250 acres (Sideham, Worthy, Tidderson, Little Rackenford) with another eleven at around 150 and as many again at less than 100 acres. Few farmers were freeholders until after 1900, but most held their farms by the old system of leases for lives, under which the farm was bought for a lump sum for up to 99 years or the lives of three named people, usually the farmer, his wife and his eldest son. This gave independence from the ground landlord; it also contributed, in the 16 th century, to much litigation over Rackenford farmers’ title to their land .

In the 17 th century there are one or two records of cottage work for the Tiverton wool mills, but otherwise the village serviced the farms, housing nonresident labour (until the 20 th century unmarried workers normally lived in) and providing, up to the 1950s, a blacksmith, tailors and bootmakers, a laundry, a thatcher and a wheelwright/carpenter, besides bakers,

grocers, a butcher with an abattoir and, later, garages. Until about 1930 Rackenford Mill ground corn on the Little Dart below the village. There are faint traces of its leat to be seen up the track which leads off to the right before the bridge.

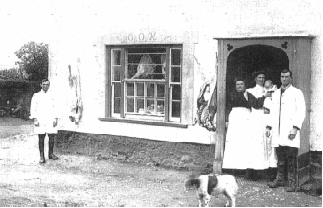

Truroes about 1900

Rackenford does not have either the soil or the climate to make mixed farming easy. Much of the land is or was moor, slowly taken in for arable crops by hard labour over the centuries. Grain was nevertheless essential for subsistence, and an early record of what Rackenford farms produced shows, in contrast to farming patterns today, that this was once at least half of their output. For the survey carried out in 1535 for Henry VIII, a revaluation of the church revenues he had taken over from Rome, the evidence of Rackenford’s priest at the time, William Jethcott, was that his total income was £19 17s 3d (a little under £20, or about four times the agricultural wage). Of this £2 10s came from working his own glebe land and another £2 1s 8d from offerings made in church, but the greater part was from tithes, paid by the farmers in kind at a rate of one tenth of any kind of farm output. This consisted of “corn” £8 17s, wool £4 14s 8d, lambs £1 14s, calves 16s calves and cheese 14s 10d. There are other snapshots of farm output over time, also from tithe issues. In 1656, in the time of the Commonwealth, Thomas Ayre of Worthy had bought the right to collect the tithes for the year. Well placed to observe the crops of his neighbour, John Gunn of East Nutcott, Mr Ayre complained of underpayments in all categories. These included wheat, rye and oats of which Mr Gunn said he had grown 11 acres on his 107 acre farm, peas which Mr Ayre had neglected to collect, so they had rotted, lambs (24 according to Mr Gunn but Mr Ayre alleged there were 40), the wool from 104 sheep (alternatively 300) and a small amount of butter and cheese. John Gunn denied having any calves, pigs, geese or colts tithable in that year though he did say there had been a small amount of honey. Whatever the truth of the evidence, this description 3 shows the increasing importance of sheep, and especially wool, to Rackenford farmers by this time. An argument in 1741 between the Rev Mr Ewens and William Cockram, the owner of Tidderson and Lower Bulworthy on the other side of the village, also lays much stress on possible sheep numbers but also

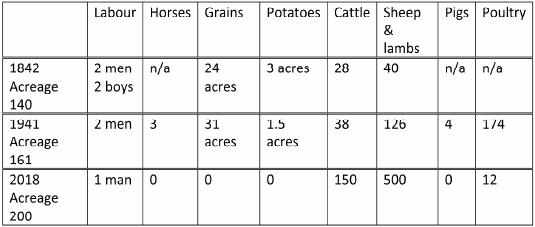

mentions horses, and for the first time turnips and potatoes 4 . In 1812 the Rev John Comins complained about the farmer at Little Rackenford’s refusal to account for any of his products, which included “divers numbers of Hens Ducks Geese Turkies Fowles and other Poultry… which have laid him Eggs and produced great numbers of young Chickens…” 5 ( Little Rackenford still does this today). Farming practices were slow to change in Devon as a whole and particularly in North Devon, where pack horses as opposed to wagons were still the main means of farm transport and oxen were used as plough teams up to the late 18 th century. Farming remained a highly labour intensive occupation up to and including the Second World War; in 1941 the wartime agricultural census 6 found no tractor on any Rackenford farm (though there was one in Creacombe). Ten years later they had become general. The greatest changes followed soon after this with the introduction of silage and of wrapping bales in plastic, enabling forage to be cut green and used throughout the winter. The main natural resource of Rackenford farms is grass, and the mixed farms of the past are now largely replaced by beef and sheep. The 140 acres of West Backstone, for example, were found at the final tithe survey in 1842 7 to be supporting 40 sheep, 10 cows and 18 young bullocks (though the surveyor was generally suspicious of Rackenford farmers’ ability to conceal their stock). Wheat, oats and potatoes were also grown and the tenant farmer employed one man and two 15 year old apprentices. In 1941 nothing much had changed except that the Berry family were owners instead of tenants, but seventy years later things were very different.

2018 In the second half of the 19 th century, in times of agricultural depression, there began to be a drift away from farm work. New opportunities were offered by the railways and the Welsh coalmines, and also by emigration, initially to the US and Canada and later to South Africa, Australia and New Zealand. Nevertheless in the 2000 Rackenford Village Appraisal farming or farming associated work still provided the largest group of jobs. Two businesses in the village haulage and contracting have mostly farming customers. Selfemployment today however includes trades whose markets extend well beyond the parish; besides mechanics, building and an electrician there is IT consultancy, forestry, charcoal burning, graphic

design, trombone repair and curtain making. The largest Rackenford employers are

currently educational, the village primary school and the Little Angels nursery opposite.

(8 shops, 12 trades with local customers)

(1 shop, 5 trades with some local customers)

The Poor

From Elizabethan times to 1834 the parish was the only source of social security. The farmers took it in turns to officiate as churchwardens and overseers of the poor; two overseers, chosen annually, collected money from the rate payers with which, if necessary, they would keep the unemployed, the old, sick and orphans from starvation. The rate payers were normally all farmers themselves, since rates were charged on occupants of over one acre. Their responsibilities only extended to people born in the parish or with “right of settlement” there. There are many arguments with surrounding parishes recorded in the Order Books of the magistrates sitting in Exeter, and in 1765 one proposed prosecution of a Rackenford overseer, Thomas Gunn, “for unlawfully & wickedly endeavouring to burthen the parish of Loxbeare with the maintenance of Elizabeth Smith and two children” by leaving them at the door of the house of his Loxbeare counterpart.

Rackenford built a small Poor House in 1817, on a site which was later a National School and is now the Community Shop. This would have been used mainly to house the old or sick with no families to support them. The main means of help was however through the parish apprentice system. From the late 18 th century it was accepted that agricultural wages were too low for a labourer to be able to feed more than two or three children at times when food prices were high. Since this was almost continually the case, the overseers were alert to keep families small, since they would otherwise have to collect even higher rates in order to pay subsidies for food. Certificates in the Devon Heritage Centre 9 show that between 1726 and 1844 123 Rackenford children were found places as parish apprentices at the age of 9 or so, the parish paying a small fee to the master. In every case but one this was a

farmer. The farms took it in turns to take an apprentice, who was fed and clothed, and

worked without wages until he or she was 21. In the peak years of poverty of 17901809 at least a third of all boys (and a smaller proportion of girls) born in Rackenford started their working lives in this way, which suggests that at least one third of the population was very poor indeed. 9In a community as small as this parents and children would not have been out of touch, and the system was at least one in which food was more evenly distributed. When the new poor law became effective in the 1840s outdoor relief in the parish was replaced by the workhouse system. Rackenford became part of the South Molton Union and parishioners unable to feed themselves were in principle all required to be sent to the workhouse there (originally on land behind South Molton church, later on the Honey Farm museum site). The Rackenford schoolmaster’s log 10 records the admission of Thomas Flew aged 11 years 3 months on May 24 1875 “never before at school.” Thomas came from Winsor Cottage on

Sideham farm, a good two miles’ walk from school; his father was a labourer working for

Mr Beedell on Sideham and his mother had died three years earlier. Thomas’ sister Mary

Jane aged 8 joined him at school in October. On March 13 1876 the entry is “Thomas and Mary Flew have left, gone to the workhouse.” Their father had died ten days earlier. Their stepmother seems to have managed to keep their 7 year old sister but for Thomas, Mary and 6 year old William there was no alternative. Mary died in the workhouse four years later; as was the regulation, she was buried in Rackenford at the parish expense. Mr Beedell however reclaimed Thomas, who was living and working at Sideham by 1881; some of the principles of the old ways seem to have survived.

Education

Church records show a small school in the village as early as 1743, largely paid for by the clergyman. Two small schools are recorded as existing in 1833, partly paid for by the parents. They probably did not teach much more than reading, but the church registers do show that two thirds of people married in Rackenford church over 183848 could sign their name. A National School for 40 children was built in 1848, replacing the Poor House. When education rates became effectively unavoidable under the 1870 Act the rate payers resolved to build a church school, which needed to cater for 80 children. The new school opened in January 1873 on a site next to the church donated by the owner of the manor. It consisted of one large room, divided into two classes; there were two fireplaces and later a coal stove in the middle. A house for the schoolmaster was attached. The present school still uses the original classroom as a hall and dining room; three new classrooms have been added to the Victorian building and the schoolmaster’s house has been merged with it.

picture were to fight in WW1. Sam Roberts, second from left in the middle row, was

killed as was David Fook, fourth in the top row.

The first schoolmaster was John Roden, who had started life as a shoemaker but managed to become a certified teacher. His wife taught needlework, but it was several years before there was a second teacher. The children’s ages ranged from 3 to 14, though education was only compulsory from 5 to 10. Mr Roden managed by means of monitresses. He found the children very backward, and entered many complaints in the school log about the failure of parents to send them at harvest times. Numbers nevertheless built up from 36 on the first day to over 80 five years later; the School Inspectors’ reports became increasingly complimentary and the managers raised Mr Roden’s salary to £100 a year. He stayed for twenty years. He was succeeded in 1892 by Alfred Snowden, whose wife was also appointed as a teacher. In 1903 they were followed by Ernest Deavin, whose surviving pictures of the village show him to have been a very talented early photographer. The school managers, after anxious discussion, appointed the first female headteacher in 1924.

Entertainment

There seem always to have been two pubs in Rackenford, judging by the victuallers’ licenses which survive from the 17 th century 12 . One was just below the village, on the site now known as Old Bell. This road is part of the toll road built from Tiverton to South Molton and Barnstaple in 1763; the Bell became the first stop for the mail coach on the way up from Tiverton, and for changing horses on the regular services which now connected Rackenford to the outside world. The inn was evidently inadequate for this and was rebuilt further up the road as The Bell Inn in about 1790. When in 1927 the brewery company which then owned The Bell decided to sell it, a group of local farmers, assisted by the rector and the owner of the manor, joined together to buy it and run it as the Rackenford Club. They would seem to have disapproved of the atmosphere at the other pub, The Stag, since among the original objects of the Club are listed “mental and moral improvement” and “rational amusement”.

The Stag is usually described as 12 th century, and indeed it is very possible that there was an ale house opposite the church site as far back as the village existed. It was not the church house, however, since a lease of 1688 refers to another house on what had been that site. The present building is probably 17 th century, and the earliest victualler’s licence to survive is 1607. In the later 18 th century the local justices held the annual victuallers’ sessions (at which the publicans together with a supporter had to give sureties for good behaviour on their premises) for the South Molton division alternatively at Witheridge and at The Stag. The attendance of thirty innkeepers and their friends must have made for some of the liveliest days in Rackenford history. Both pubs were important centres of social life. Although it was not until the 1950s that women were to be seen in either bar, they were quite often in the hands of landladies, Mrs Radford of The Bell being a particularly well known cook in the 1870s. Both establishments were able to organise large dinners, for 50 or more, which are reported throughout the 19th century. The Stag was run by the Turner family for four generations over more than 100 years, starting with Robert Turner in 1830; Mrs Louisa Turner bought the freehold from the manor in 1907 during her nearly 40 year occupancy. Annual pony races (an early form of point to point) were a feature from the mid 19th century, and centred on The Bell since they were held on the field below the manor. Ploughing matches, which also included hedging and rope and spar making classes, began to be organised at about the same time. The Stag specialised in pigeon shoots, and both inns were the scene of regular meets of the Tiverton Foxhounds, hunting being a major local interest, of tithe dinners, harvest festival suppers and occasional political meetings.

An annual village revel was still being celebrated on June 12 in 1876, when Mr Roden complained about absenteeism among the children in the afternoon. Newspaper reports of all these events often describe the concluding dinners as ending with singing, and the folk singing tradition was still alive in Rackenford when Cecil Sharp paid two visits in 1904 and 1905 and recorded six singers, all living in the middle of the village. Church and chapel both had teas and outings, the latter as far as the seaside once motor transport became available in the 1930s, and much fund raising in the form of sales of work, whist drives, dances and concerts went on throughout the year to finance these trips. The School hall was at first the main location for events, though in the early 1900s a wooden hall was built to house the stock of the seed, fertilizer and manure business which was run from Boyces 12(next to The Stag) by the Gunn family together with a grocery and a Post Office. It was soon realised that Mr Gunn’s stock could be cleared out in summer to make room for a dance or a concert, and this new resource, known as the Gaiety Hall (approximately on the site of Shielings, behind Nobys opposite the School) survived till 1970. The brewery which at that point owned The Stag built the extension known as The Stag hall shortly afterwards, particularly for use as a skittle alley, and it took over the main function of hosting village

events.

For a brief time from the 1930s the village was linked by two buses a week to Tiverton and South Molton, giving new access to entertainment further afield. General private car ownership had arrived and public transport mainly gone by the 1980s, when the A361 was built to join the M5 motorway to Barnstaple, passing Tiverton and cutting through the NE corner of Rackenford parish. This great change in the accessibility of the outside world has meant that many people work outside the parish itself, but it has not ended the lively culture of self help and self amusement, as visitors to any fund raising event may discover.

Church and Chapel

There is no evidence of a Saxon church at Rackenford, though it is likely that there was one, even if only of wood and thatch. In any case at some early point, whether before or after 1066, the owners of all the separate holdings in what now constitutes the parish must have agreed to join in the support of one parish church. A tradition, recorded in the 18th century 14 , was that there were once also chapels at Little Rackenford and Sideham, and this may account for some confusing early records as to who owned the advowson (rights to appoint the priest and other dues) which were attributed to more than one priory before being finally awarded to the de Sidehams. There was probably a stone church before 1235, when Robert de Sideham got his permission to hold a fair on All Saints Day (November 1) which is the church’s dedication.

There are no traces of a 12 th or 13 th century building; the arch to the south door is 14th century but the present church is mainly of the 1400s. The original dedication to All Saints was changed to Holy Trinity after the reformation, but changed back again in the late 18th century.

A strange feature of the church is the lack of symmetry which comes from different additions or rebuilds; it seems not to have concerned those responsible that the east window ceased to be in the middle of the chancel wall, or that the chancel ceiling is further out of line with that. The wet and windy site explains repeated repairs and also probably the scarcity of surviving monuments, although there is an interesting wooden one, carved in pine, to Arthur Chamberlain, cousin of the prime minister and owner of the manor from

192841. The main recorded changes 15 are the reseating with box pews in 1738, the removal of the remains of the screen in 1785 and the rebuilding of the south wall in 1827. A gallery was installed at some point in the 18 th century to provide more seating, which would have been an urgent need for the rising population. In 1870 funds were found for a good organ from the London makers, Messrs Bevington. By the time of the major late Victorian restoration (1897) 16 total numbers had dropped again, and the Bible Christian

chapel was also catering for the large proportion of residents who had left the Church of England. This restoration took the gallery down, and removed the box pews, in which it was complained that “children finished their Sunday dinners and old men slept” 17 . The largest pew of all, belonging to the manor, was demolished in order to move the organ from the west end to its present position and to create the small vestry. Many layers of white wash were cleaned off the oak wagon roof with its carved bosses and angels. These once extended into the chancel, but were lost in an earlier repair. Other features to admire are the great west arch and the little mouldings round the capitals, looking like berries with leaves, though the one at the east has an unusual starshaped pattern. Rackenford lost its priest in the Black Death of 1348 18 and a later rector, Lewis Crowther, died in what was probably an outbreak of plague in the village in 1596. The rectors from about that time lived in the Rectory across the common to the west of the church, and farmed the 48 acres of Glebe which went with it. A puritan (James Kingwell, son of a Tiverton shoemaker) was appointed to the living, without any local protest, during the Commonwealth in 1643. Information in the church describes others, such as the Rev John Westmoreland, who inexplicably disappeared in 1723, and the 18 th century Rev Thomas Barnes, who explained to the bishop that his wife was “unable to bear ye severity of ye winter’s cold” in Rackenford, thus obliging him to live in Tiverton. All of these were able to respond to the regular Bishop’s Enquiries as to whether their parish included any Roman Catholics or dissenters that there were no such persons. In 1820, however, a licence 19 was issued to David Rawle, a Bible Christian and a farrier by profession, who with his brother Michael had moved into Rackenford from Lynton, to use his cottage for religious meetings. Bible Christian conversions followed rapidly. Michael Rawle married into a Rackenford farming family of Reeds, and his daughter into the Matthews, blacksmiths in the village for several generations. (This gave the village the Rawle Matthews veterinary practice, which lasted into the next century.) The holding known as Bradford at the entry to the village was

acquired on which to build a farmhouse and a chapel (Ebenezer) in 1848. The religious

census taken in March 1851 showed that there were 240 church attendances on a Rackenford

Sunday and 175 chapel. The Rectory, the Ebenezer chapel and its Sunday school are all now private houses.

Trinity Well Described as “a never failing spring of pure water” in White’s Directory of 1850, this was originally a holy well, reputed to cure problems with eyesight. It became the main well for the village, its water being held to be far superior for laundry to that from the more central one outside Old Wellhouse (a little way up the other side of the road from The Stag). Water was fetched on Sunday nights in buckets, baths and bowls, ready for the Monday wash, and the well was a regular meeting place, as could be remembered until very recently. A new pump was installed at the expense of Colonel Durnford of the manor in 1903, protected by a rustic thatch and timber structure. The starched collars and pinafores of the children in the photograph of this are evidence of the high standards of laundry in Rackenford in those days, when their mothers would have boiled the water for a wash in a copper and heated their irons on the fire.

When mains water arrived in the 1950s (electricity followed in 1960) the Water Board capped the well off. The Parish Council discussed restoring it for many years, and finally succeeded in getting a grant from Awards for All to start the work in 2008. Many people donated money or time to the project. The rebuilt pump house is the same shape as the last, but cob has been used instead of timber as more likely to last and also more likely to have been what an earlier structure would have looked like.

Families

The Rackenford church registers start in 1561 (marriages), 1577 (burials) and 1597 (christenings), but there are gaps in the early years. Bible Christian baptisms entered in the Methodist Tiverton circuit register run from 1844. The registers show the main Rackenford clans – Notts, Parkers, Crooks, Gunns, Veyseys, Thornes, Norrishes, Turners, Ayres, Blackfords, Pincombes – but also that very few of the names last as long as four hundred years. The Ayres of Worthy were unusual in owning it (and other farms) for seven generations from 1536, but none are left in the parish today. The Gunns first appear in the register in 1625 and were farmers at East Nutcott in 1657; they later were farming at Middlecott, Mogworthy and Bulworthy, and the last of the family to live in Rackenford ran a corn business together with a Post Office shop at Boyces in the middle of the village until the 1950s.

Most of the other families came later or disappeared sooner. All these names are of both farmers and farm labourers, often related in a relatively flexible social system, but there are a few – notably the Flews and the Kents– who seem invariably to have been labourers and often in need of parish support. They too have vanished, to better things. Among the many families who have owned the manor the Chamberlains and the Eldons both connected Rackenford briefly to the outside world. Arthur Chamberlain, cousin of the prime minister, owned it from the late 1920s to 1941. Neville Chamberlain visited for shooting parties. Lord Eldon bought the manor in 1942, and during the next 20 years Rackenford saw visits from the Queen and her sister as children and later the Queen Mother. The Eldons are still remembered for their support for hunting and for village activities.

World War 1 and 2

The Rackenford war memorial, put up at the crossroads at the entrance to the village in 1921, shows the names of eight men who died in the First World War and the further 38 who served. It includes the hamlet of Creacombe and the names represent over half of the adult male population of the two parishes. Conscription began in January 1915 of all

unmarried males aged 18 to 41 and was later extended to the married. Some exemptions were allowed on the basis that a farm needed at least one male worker other than the farmer himself. At least four of the Rackenford men were already in the army, as was Captain Boles from the manor, and a few were volunteers with the Devon Yeomanry, who were called up as soon as war broke out. For almost all the rest, life other than on a Devon farm was virtually unknown, and most will never have been further away than Exeter or even Tiverton.

Most of those who died were very young. The first death was of Charles Nott, one of the sons of the farmer at Worthy, who had been working at home; he was 26. Four died in France in 1916; Fred Greenslade from Higher Thorne, aged 23, Fred Pincombe from Higher Queen Dart where he had been a wagoner, aged 21, Sam Roberts aged 21 on the first day of the Somme and his brother John (Frank) aged 25 two months later. Both the Roberts brothers, brought up at Winsor Cottage at Sideham, had been farm labourers before joining the army as regulars; they were among the 30 serving grandsons of John Roberts, an agricultural labourer from Witheridge 20 . David Fook, son of the village carpenter, had been working on Lower Bulworthy; he was 23 when he died in Flanders in 1917 and the only one to have been married except for Rackenford’s rector, Gerald Lester, who joined as an army chaplain at the end of the war and died of pneumonia in Rouen. 20Harry Boundy, son of the village bootmaker, who had been a carter at Higher Mogworthy , was older, 42 when he died of his wounds in 1918. Nearly all of those who died and those who served were at Rackenford School; probably all of the boys in the photograph of “perfect attenders”. The experiences of the 38 who did come back, ranging through Palestine, two years in Salonika, prison camps in France and a minesweeping flotilla in the North Sea, are an incalculable element in Rackenford life thereafter. The Second World War in some ways had far less impact; there are only ten names on the War Memorial and only one of those was killed. However a large proportion of the male population joined the Home Guard; there are 31 in the group photograph taken early on. This war also came nearer; fire watching was organised from the church tower, the army installed a searchlight station opposite Higher Thorne, and Italian prisoners of war lived in a local camp from which they were employed to dig up Creacombe moor. A German fighter plane crashed in the woods by Bradford Barton, just on the parish boundary (an unexploded bomb picked up by one of the farmer’s sons was found in his bedroom cupboard 50 years later). There were also the evacuees. A junior school from Erith was evacuated to Rackenford together with one of its teachers, who at first taught them separately in the Gaiety Hall, since they outnumbered

the 39 school children of Rackenford. By the summer of 1941 over 60 town children were being looked after in the village and on the farms. Joyce Harden, then Cronin, recalls the train journey to South Molton followed by a bus to the unknown destination of Rackenford, and the humiliation of being lined up around the school hall for the residents to make their choices of child. However she then experienced an idyllic summer at Mogworthy, and there were several other evacuees whose time on Rackenford farms led them to revisit regularly ever afterwards.

Buildings

The oldest building to survive is of course the church. In the village The Stag and some of the houses on the east side of the street (Myrtle Cottage, now the Little Angels nursery, Baters, Nobys and South View) are at least partly 17th century. Many of the cottages are older than they look and were originally thatched. The only listed buildings in the parish are the church, the chapel, the Old Rectory (17 th /18 th century), The Stag, Rackenford Manor (a c1812 rebuild with a 1929 wing) and Middlecott (17th century). Most farmhouses were rebuilt in the late 19th century, often after fires destroyed thatched roofs, but Town End (at the bottom of the village), Higher Mogworthy and Tiddyport are older, and Higher Thorne and West Backstone are both around 1800. Meadow View, the terrace of eight houses at

the entrance to the village, was built by the South Molton Rural District Council in stages from 1951 and is an outstanding example of good public design. Nearly all of it is now privately owned.

Of the large increase in housing over the last 100 years the greater part is accounted for by cottages and bungalows on the farms. The 30 or so new houses in the village have been partly balanced by the loss of some small cottages on their sites. Apart from Meadow View the layout of the village remains much as it always was, most houses facing the one main street and with gardens to the back. Additional houses have from time to time been built in the larger garden spaces, but nearly all houses still have a green view to the back, either of the common or of fields, and this is a planning principle which the parish council managed to have incorporated in the Rackenford section of the current North Devon plan.

The main change to the village is in its activities; as the map showing the village street in the 1940s shows, shops and local trades were once plentiful. The little building with Gothic windows in which Rackenford’s only shop is now to be found was the school building ofAfter it ceased to be a school it was used for Vestry meetings. A later owner of the manor, Francis Boles, set it up as a reading room for boys at work but too young for the pub, where they could find a fire, newspapers and games. When he died he left it to Rackenford church. It became increasingly derelict, and when in 2003 Rackenford was threatened with losing its last shop, run from one room and not conforming to health and safety standards, the Rackenford Village Shop Company was formed to buy the building, restore it and equip it as a shop. The total cost of £75,000 was met by grants, loans, and contributions and fund raising by the community. Nearly every household is a member of the Company. Since 2008 the Company has run the Shop itself on a volunteer basis, renting a counter to the Post Office. An average of 16 people now operate a very successful enterprise. More volunteers (and customers) are always welcome.

Bibliography

Marshall, William, 1796 Rural Economy of the West of England (David and Charles reprint, Newton Abbott)

Vancouver, Charles, 1808 General View of the Agriculture of the County of Devon (David and Charles)

Way, Robert E 18361912, unpublished ms c1880s Rackenford a parish with an History.

Son and grandson of Rackenford’s parish clerks, he would have had access to the parish records kept by these, partly lost when the Rectory was sold in 1965, and hence provides dates not elsewhere available.

Other unpublished notes on Rackenford by Arthur Holloway and his son in law, the Rev Christopher Tull, vicar from 1968, evidently drew on this.

Notes and references

Devon Heritage Centre (DHC), Public Record Office (PRO), Transactions of the Devonshire Association (TDA)

1. Testa de Nevil.

2. TDA 131 December 1999 p123138; Child, Sarah “Rackenford goes to Chancery:

an outbreak of litigation in an Elizabethan rural parish.”

3. PRO E112/296/117 Ayre v Gunn 1656

4. PRO E112/1104/175 Ewens v Cockram 1741

5. PRO E112/524 Comins v Tidboald 1812

6. PRO MAF32/689/312

7. PRO 1R18/1462

8. DHC 9/44 Quarter Sessions Process Book Christmas 1765

9. DHC 2984A/1/PO13100 and TDA 136 December 2004 p135148; Child, Sarah

“Parish Apprentices in Rackenford 17281844

10. DHC 7223C/EFL/1

11. DHC Chanter225 B631 Bishops Enquiries 1744

12. DHC QS 62/15/3/110, 62/14/41/83

13. Vaughan Williams Memorial Library; Roud Collection and Broadside indexes

14. See 11 above and Robert E Way MS notes

15. See MS notes Robert E Way, Arthur Holloway and Rev Christopher Tull

16. DHC 2984 add A/PW111

17. See 15 above

18. DHC Register of Bishop Grandisson

19. DHC DEX/12/a/2/352

20. 2018 Roberts, Paul

“ History Maker John Roberts, the man with 30 grandsons in the Great War” p9097.

Text by Sarah Child, graphics by Viv Calderbank (Topical Design)

editorial comment by Graham Fennell

Old photographs with thanks to Bill Clark, Betty Kirby, Hilda Nott, Cyril Blackford, Vera Sutton, Bob Berry and other Rackenford residents.

The author is happy to provide further references to the documents and sources used for this booklet and also to help anyone researching their Rackenford ancestors.

© Copyright Sarah Child 2019 West Backstone, Rackenford, Devon EX16 8EF

Hard copies of this book are available from:

RACKENFORD COMMUNITY SHOP

or may be ordered by email: rackenford.shop@btconnect.com

Tel: 01884 881740

A pdf version is available here